Most people accept the idea that we are descended from earlier primates. But descended from fish? That might seem to be a stretch. In Your Inner Fish: A Journey into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body (2008), Neil Shubin makes a vivid case. He traces our body parts back to fish and beyond. And he comments passionately on the beauty and unity of life’s development over billions of years.

(shubinlab.uchicago.edu

Along the way, Shubin narrates the painstaking detective work of the paleontologist. He weaves the opening chapters around his own years in the barren Arctic as he helped to discover, in 2004, the 375-million-year-old fossil of a missing link between fish and amphibians.

The discovery of Tiktaalik, Inuit for “large freshwater fish,” was exciting for several reasons:

All fish prior to Tiktaalik have a set of bones that attach the skull to the shoulder, so that every time the animal bends its body, it also bent its head. Tiktaalik is different. The head is completely free of the shoulder. This whole arrangement is shared with amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, including us. The entire shift can be traced to the loss of a few small bones in a fish like Tiktaalik. (p. 26 in the Vintage paperback edition).

Say hello to our neck.

(avonapbiology.wikispaces.com)

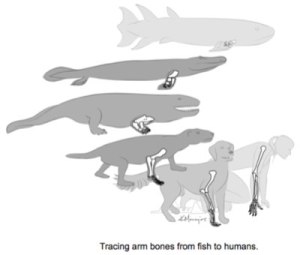

There was another surprise about Tiktaalik. Earlier fish had fins with bones that were the ancestors of our arms and fingers. To these early forearms and fingers Tiktaalik added small bones that were, in fact, the earliest wrists. These crude wrists mean that Tiktaalik, as Shubin puts it, “was capable of doing push-ups….The wrist was able to bend to make the fish’s ‘palm’ lie flat against the ground….Tiktaalik was likely built to navigate the bottom and shallows of streams or ponds, and even to flop around on the mudflats along the banks” (39-40).

So Tiktaalik had fins capable of supporting the body—these were the first limbs for moving on land. Since then, the same structure has appeared in not only the arms, legs, and hands of humans and other mammals but also in the wings and flippers of bats, penguins, birds, and whales. In all these, one bone is attached to the torso (in us, the upper arm bone and the upper leg bone), followed by two bones, followed by little bones (wrists and ankles), followed by smaller fingers and toes.

(noreligionblog.wordpress.com)

Shubin’s other chapters trace the development of teeth, heads, noses, eyes, ears, and even bodies themselves, which emerged 3.5 billion years ago. In each chapter at some point, Shubin pauses to explain his appreciation of the patterns he is describing. “Beauty” and “beautiful” are common words in the book. The anatomy of the head “is deeply mesmerizing, in fact, beautiful. One of the joys of science is that, on occasion, we see a pattern that reveals the order in what initially seems chaotic. A jumble becomes part of a simple plan, and you feel you are seeing right through something to find its essence” (82). Echoing Carl Sagan’s thought that “looking at the stars is like looking back in time,” Shubin says the same about the human body. “If you know how to look, our body becomes a time capsule that, when opened, tells of critical moments in the history of our planet and of a distant past in ancient oceans, streams, and forests” (184).

I would guess that many scientists feel the same way about looking into the essences behind the apparent chaos. But not many write about it so well. That’s unfortunate, because I think that if they did, more non-scientists would value what our biological history can tell us about who we are and what our lives mean.