How have we humans come to be so skillful at smiling, laughing, and crying? Other notable human behaviors – reproducing, fighting, sharing, hunting – have easily visible predecessors among most animals. But our repertoire of daily grins, laughs, and tears – except for some vaguely similar expressions among chimps, dogs, and rats – is unique. We express life’s joys and sorrows in ways that seem to have little ancestry.

But neuroscientist Michael Graziano proposes that we smile, laugh, and cry in useful mimicry of a protective, cringing reflex that is millions of years old.

In The Spaces Between Us: A Story of Neuroscience, Evolution, and Human Nature (2018), Graziano describes his team’s years of research at Princeton on how the brain monitors the personal space around us. This flexible buffer zone can extend out to the edges of the car we are driving or to our child who is leaning over a ledge. The buffer also shrinks to the physical closeness we allow with those we trust and even disappears altogether for pair bonding and sex. The buffer is a protective, not a social space. “Personal space is all about the zone where you keep people out, not the zone where you invite people in” (Kindle location 472).

So where do smiling, laughing, and crying come in? Such expressive reactions are rooted in an ancient cringe posture that people still take on when their protective zone is suddenly and dangerously threatened – by seeing a stone thrown at them, for example. The posture reflects the brain’s first priorities: protect the eyes and the abdomen. “The forehead is mobilized downward and the cheeks are mobilized upward, dragging the upper lip with them.” As a result, the teeth are exposed. Hands cover the abdomen, the body hunches down, shoulders rise.

We think of a smile as being about teeth, but the display of teeth is only a consequence of the cheeks lifting upward to protect the eyes. Still, the sight of this wincing “smile” may have reassured an early enemy that the individual in the cringe posture was not a threat. But the potential victim learned even more: that the facial expression could be imitated, mimicked, in order to ward off injury, to play it safe. Millions of years later, we smile.

Graziano states his point carefully. “…[T]o be clear, the human smile is not a defensive cringe. When you smile, you are not thereby protecting your eyes from a flying stone. You’re not expressing fear. You’re not anticipating an attack. But the evolutionary precursor of a smile is a defensive cringe that protects the eyes in folds of skin. A smile is an evolutionary mimic” (2255).

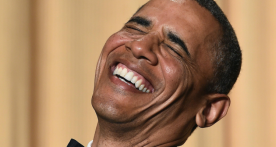

While the smile mimics a gesture that might have headed off a conflict before it started, laughter may have emerged as a way to prevent harmless play-fighting already in progress from getting too serious. Graziano connects laughter with tickling. When a child is tickled, the hand of the tickler moves into the child’s protective space, the cringe reaction begins to sound the alarm, the hand reaches an area of sensitive skin and “the touch evokes a full-blown laughter…an entire collection of alarm shrieks, defensive blocking and retracting, a pursing of skin around the eyes, upward bunching of the cheeks, upper lip pulling up, and secretion of tears”(2316). Laughter evolved from such an alarm reaction that tells a play-opponent that yes, you’ve touched me, touché, now that’s enough. Like the smile, laughter gradually became a social signal, read by others, mimicked by those who want to signal their good-natured agreeableness.

Graziano acknowledges that such speculation does not explain the many types of laughter – or the nature of humor itself. But it does suggest why, after the long road of its evolution, full and hearty laughter shares many of the facial markers of the defensive cringe.

Crying, unlike smiling and laughing, adapts the cringe response to the loser’s need for friendly resolution after an all-out fight is over. After an attack, a primate victor often comforts the loser. The loser’s cringing, moaning, and tears signal not only surrender but a plea to restore amity. After a million years of such reactions, we mimic the post-drubbing defensive cringe as a way to express pain and ask for consolation – even when we are crying alone.

Graziano’s book is very clear, very engaging, and at times very personal. And I value knowing how laughter and tears both link us to early ancestors while also displaying such an evolutionary distance from the original reflex.